Edwina

Currie: Isn't it time we Scousers admitted some home truths?

By Edwina Currie

Last updated

at 1:16 AM on 14th August 2008

Edwina Currie: 'You seek energy, creativity, cutting-edge employment?

Head for London, not Liverpool'

The policy

Exchange, said to be David Cameron's favourite think-tank, has really

set the cat among the pigeons with its latest report.

Northern cities such as Liverpool, Bradford and Sunderland are beyond

saving, it says.

The millions

spent on regeneration have been wasted; restrictions on building

down south should be lifted and people encouraged to move to 'economic

powerhouses' such as London, Oxford and Cambridge, otherwise they

risk being 'trapped' in places which have 'little prospect of offering

their residents the standard of living to which they aspire.'

Cue howls of protest, rather as one would expect.

David Cameron,

touring the North this week, has denounced the report as 'insane'.

Regeneration,

he declares, has been a key Conservative theme over the past three

years. Of course it has.

After all, David

is hunting votes beyond the Tory heartlands and is dangling the

prospect of yet more government handouts as bait.

But since there

hasn't been a Tory MP in Liverpool since I was a teenager, he probably

shouldn't bother. I reckon the report is uttering only home truths,

unpalatable though they may be to politicians of every hue.

If government efforts to help northern cities since the 1950s had

succeeded, then there would be no gap in living standards, or employment,

or educational achievement, or health - yet the gaps have persisted

and in many cases widened.

You hope to

live a long life? Try Hampshire, not Hull. You dream of a three-car

household? That's Surrey, not Sunderland.

You seek energy,

creativity, cutting-edge employment? Head for London, not Liverpool.

That's what

I did, 40 years ago, and I have never felt the urge to move back

to my home town of Liverpool.

I grew up in

Childwall, a district in the south-east of the city, with Mum and

Dad, and my brother Henry, in an ordinary semi.

My father had

a gentleman's tailoring business in the heart of the city in Williamson

Square, making uniforms for sea captains.

In 1994 we held

a reunion of my old school, the Liverpool Institute High School

for Girls, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of its foundation,

and I discovered that the entire sixth form of my day had migrated,

most of them down south; only one girl still lived in the 'Pool,

and she'd returned to live with her parents.

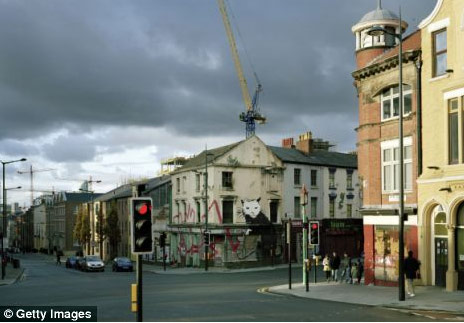

Liverpool

landscape: Standards of living have 'little prospect' of improving

Worst of all, the loony-Left city council under Derek Hatton had

closed our wonderful school, and the companion boys' school where

Beatles Paul McCartney and George Harrison had been pupils.

State grammar

schools with their cult of excellence didn't fit into the council's

'regeneration' plans, did they?

When I was

a kid, Liverpool had 800,000 residents and was still a world-renowned

seaport.

It was a rumbustious

place, with a fabulous music scene, majestic public buildings, international

business such as insurance and shipbuilding; we watched the Cunard

flagships setting off for New York and dreamed of sailing away ourselves

some day.

Escape, that's

what we had in mind. It was an extraordinarily prosperous place

- and the sky seemed to be the limit.

But by the time

I had my 'ticket to ride' in the form of a scholarship to Oxford,

the port had lost its reputation as the Atlantic shipping trade

died and endless strikes finished it off.

Meanwhile, Liverpool

itself was haemorrhaging a thousand people a week. Now, the city's

population is down to 439,000; a quarter of its residents are on

benefits, the highest proportion in the country, while on a Saturday

night Liverpool has the highest rate of emergency hospital admissions

for alcohol-related injuries in England.

The Beatles:

Liverpool's most famous sons

I still go back occasionally. There's definitely still a lot to

love about Liverpool.

Scousers are incredibly warm-hearted, funny and generous. And they

certainly know how to have fun.

But it isn't

long before I get a sinking feeling, and remember why I left my

hometown.

Like emerging

from Lime Street Station in February - at what was the beginning

of Liverpool's year as the European Capital of Culture - to find

pavements dug up and underpasses closed. Hardly a centre of cultural

excellence.

'They'll be

ready for it this time next year,' I muttered.

Or when international

golf came to Lytham St Annes, up the road. I asked my taxi driver

about it: 'Bloody Americans,' he complained, hardly the attitude

to welcome high-spending foreign visitors.

In December

2006 I went to a Christmas dinner at the Adelphi hotel, once the

Claridge's of Liverpool, only to find a notice in the bedroom saying,

'All electrical items removed from this room to be paid for' as

if it were a cheap hostel where all its guests were thieves.

Hardly welcoming

surroundings for the traveller searching out the legendary Liverpool.

My heart goes

out to the local people. They've been conned by successive governments,

both Tory and Labour, and by the Liberal Democrats who have run

the council more recently.

Government money

won't turn things round. Only your own initiative will do that.

And what the report says is so true it shouldn't need restating:

that if a city has lost its raison d'être, whatever it was

that brought it into existence in the first place, then shedloads

of taxpayers' largesse won't turn back the clock.

TV's The

Liver Birds: A celebration of Scouse humour

Far better, and cheaper, if workers go to where the jobs are, rather

than trying to blackmail or subsidise business to move to where

it does not want to go.

In fact, that's what many individuals have been doing for decades.

Like me, they look at the lack of opportunities, and they vote with

their feet.

The problem

is, government interference makes things worse. Local politicians

become adept at holding out their hands, palm upwards; the skills

thus valued are how to fill in forms and how to spin a convincing

tale of woe and continuing need, instead of figuring out what talents

their residents have, or need to develop, to compete in the modern

world.

Those with imagination

or ambition or a determination to do things for themselves don't

fit - take Liverpool's most famous living son, Sir Paul McCartney.

His success came to him only in London - and there he remains. I

am not talking through my hat; I've been through this before, when

I was an MP.

As the pits

closed down in my South Derbyshire constituency, unemployment began

to rise.

We had lived

on state subsidies for decades and things had to change. But the

locals were skilled, hard-working, and open to ideas.

They were also

adaptable, and willing to take on whatever challenges were flung

at them. They did not believe in going on strike and were determined

not to live on handouts.

Along came car

manufacturer Toyota, and hey presto! The new factory meant Derbyshire

was making cars, and the area gleams with a new prosperity.

Population

has risen so much that there'll be an additional parliamentary seat

come the next election. And none of it was done with public money,

not a penny.

If I were in

charge in Liverpool today I would be reading this report with interest.

I'd be making inquiries: what do outsiders come to Liverpool for?

What do they like when they arrive? How can we persuade them to

stay, and spend money here?

I'd be asking

the two Liverpool universities to see what happens to their graduates,

and what might persuade them to seek employment in the city.

I'd not be squeamish about asking what they hate, and taking action

about it: the crime, the dirt, the ignorance, the shortage of decent

places to stay and to eat, the dereliction on every side.

Plenty of cities

set examples of revival through their own efforts, from Manchester

to New York. It can be done.

And as someone

who still loves Liverpool, my message to my fellow Scousers would

be: get on and do the same.

Previous Page

Click

here to print this page

|